Cystoid Macular Edema

What is Cystoid Macular Edema?

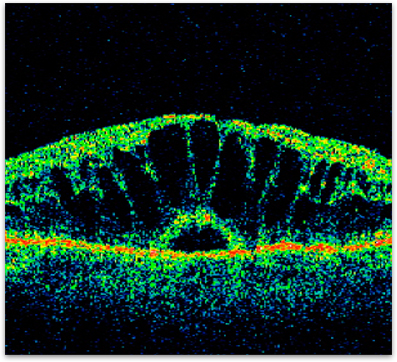

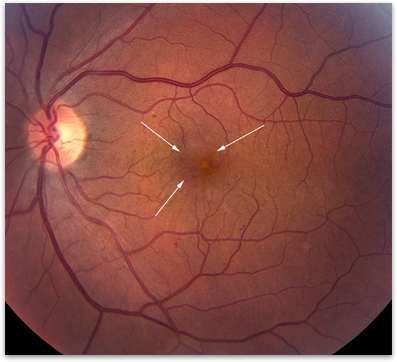

The retina is the layer of specialized nerve tissue that lines the back of the eye and allows you to see. The macula is the part of the retina that is responsible for your detailed vision and lies at the very center of the retina. Cystoid macular edema (CME) is a painless disorder in which swelling develops in the macula. As the swelling increases, multiple fluid filled cysts develop in the macula, causing vision loss and distortion (figure 1,2).

What causes Cystoid Macular Edema and who is at risk?

There are two basic mechanisms that can cause CME. One cause is vitreous traction and the other is inflammation. With vitreous traction, there is an abnormal connection between the vitreous (the gel that fills the eye) and the macula. In this situation the vitreous gel tugs on the macula causing the cystoid macular edema. The other cause of CME, inflammation, is by far more common. The inflammation can be caused by an eye injury, eye surgery, or a number of other eye diseases. It most commonly occurs after cataract surgery. In fact about 3% of all cataract surgery patients will have some decrease in vision from cystoid macular edema.

What are the symptoms of CME?

Since the macula is responsible for fine detailed vision, blurriness is the most common symptom. As the swelling in the macula increases, images can become distorted. If the cystoid macular edema is very mild there may be no symptoms or visual complaints at all.

How is CME diagnosed?

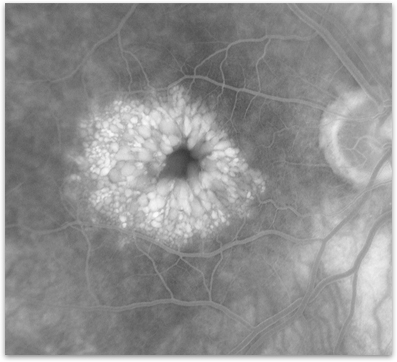

Your retina specialist can detect cystoid macular edema by examining your retina during a dilated eye exam. A retinal scan called optical coherence tomography (OCT) is used to document the amount and extent of retinal swelling (figure 1). OCT can also be used to follow the response to treatment. A photographic test called a fluorescein angiogram is very useful in assessing how much fluid is leaking into the macula and can help to identify the underlying reason for the cystoid macular edema. For this test, fluorescein dye is injected into a peripheral vein in the hand or forearm. A series of photographs is taken of the retina as the dye passes through its blood vessels (figure 3).

How is CME treated?

There are many different treatments available for cystoid macular edema. The treatment is individualized depending on the severity of the swelling and the specific diagnosis. Typically, CME is treated with anti-inflammatory medications, administered in various forms from eye drops to injections. In many cases, steroid treatments result in dramatic visual improvement, but in other cases there is little or no improvement. In these more challenging cases, other medications, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or diuretics, may be beneficial. If the CME does not respond to medical therapy and there is evidence that the vitreous is tugging on the macula, surgery can be performed. As in the case of medical treatment, some patients respond very well to the surgery and recover good vision, while others experience little or no improvement. It is not possible to predict how long it may take for CME to respond to treatment. Most cases resolve within several weeks to a few months, however some cases require an even longer period of treatment.

What is the long-term impact of CME on my vision?

Cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery usually has an excellent prognosis with the majority of cases responding to medical treatment. Once the CME resolves, the vision typically returns back to normal. Some CME that becomes chronic, lasting years, can lead to permanent vision loss. Even if treatment is not successful, or the macula becomes damaged, the peripheral or side vision is usually not affected.

Figure 1. OCT of cystoid macular edema showing the large ‘cyst-like’ collections of fluid in the retina.

Figure 2. Photograph of a macula affected by cystoid macular edema (arrows showing cystic spaces).

Figure 3. Fluorescein angiogram of an eye with cystoid macular edema showing the white dye collecting in the center of the macula.